|

|

|

SAQQARA |

NETJERYKHET / DJOSER

HORUS NETJERYKHET / NETJERYKHET RANWB

It cannot be denied that Khasekhemwy and Netjerykhet were outstanding kings during whose reigns the Egyptian State definitively came out of its long formative phase to enter the maturity which would produce majestic achievements in administration, technology, architecture, 'arts'. Yet the scarcity of monuments from the reigns of their followers undoubtedly reveals some kind of contraction if not a crisis, despite arguably one of a different character than that afflicting the middle part of the Second Dynasty.

Without Djoser's reign's archaeological evidence, the Third Dynasty would have been quite a historical vacuum.

Djoser is one of the most important (and 'renowned') king of the Old Kingdom and of the whole history of Egypt. There are many important high dignitaries known from this reign by inscriptions in North Saqqara as well as in Upper Egypt [cf. Helck, Thinitenzeit, 1987]; various private statues are attributed to his reign by style or epigraphic comparisons (Vandier, Manuel I; Weill, IIe et IIIe dynasties). The fact that Imhotep lived during Djoser's reign (and possibly also during Sekhemekhet's one) made both the king and (especially) his chancellor/architect the earliest individuals to have been object of worship in the later history of Egypt (see Wildung, Die Rolle, 1967; id., Imhotep und Amenhotep; Baud, Djéser et la IIIe dynastie, 2002, chapt. 3). In Late Period, Imhotep was deified and several bronze figurines and inscriptions have been found dedicated to him, particularly at North Saqqara.

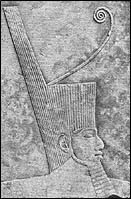

His lord, Djoser, must have enjoyed an outstanding favor in the cult as well, as attested by later 'portraits' of his (Tanis ?, see below; Saqqara, Bronze plaque relief of Amon, JEA 53, 1967, pl. 26.4 -suggested by H.S. Smith to resemble Djoser's reliefs-; Saqqara, Dyn. 30 ? statue BM EA941, Baines-Riggs, in: JEA 87, 2001, 103-118, strictly inspired to the Serdab Statue of Djoser Cairo JdE 49158; Netjerykhet's serekh on the base of a statuette of Ptah from Saqqara, ibid., pl. XV, 2-3).

We may even add the NK hieratic inscriptions of the SPC, the traditions preserved on papyri (Westacar), the copy grids left on two of the six panels of the Step Pyramid Complex galleries, the Sehel stela and many more clues showing the depth of the historical and cultural mark this sovereign impressed on the minds of the Egyptians, the persistence of his name in their memory.

Indeed the relevancy, the favour and the cult acknowledged in later periods must have depended, certainly for a good part, not only on the outstanding role that Djoser and Imhotep had by their time but mostly on the magnificence of the Saqqara Complex: it was a commonly visited monument through the ages (NK hieratic graffiti, cf. Step Pyramid 77ff.) and the 26th Dynasty pharaohs realized the excavation of the pillared gallery which connects the southern court to the shaft which opens underneath the Step Pyramid base (see the photographs at the bottom of this page) down to the burial bunker-like chamber.As we have stated about Sanakht-Nebka, it is still difficult to understand whether Netjerykhet was the beginner of this dynasty or the second king. The first hypothesis has been recently preferred but some doubts still remain. I am convinced that Netjerykhet was Khasekhemwy and Nimaathapy's son, but I also think that a reign by a brother (?) of his could have preceeded his own one. I admit that: 1) the proofs for this statement are not direct ones, but derive from the difficulty to place Sanakht elsewhere (cf. August 2007 Update in Sanakht's page); 2) there do exist proofs of the contrary hypothesis, namely the presence of seal impressions of Netjeryhet in Khasekhemwy's tomb (V) and funerary enclosure (Shunet ez Zebib) at Abydos; but as we have seen (Sanakht) the apparent direct succession Qaa-Hotepsekhemwy that the latter's seal impressions in the former's tomb should prove, did not happen in reality (2 or 3 ephemeral kings likely reigned after Horus Qa'a's demise).

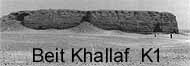

[Note: the seal impression Wilkinson (E.D.E. 1999, 95) mentions as found in Khasekhemwy's Abydos tomb V only shows the sign 'ntr' which could also be reconstructed as Ninetjer 's horus name (Kahl 1994, Quellen 2099); certainly of Netjerykhet's reign is instead the specimen recently found by the German mission (MDAIK 54, pl. 15 b)]. The biggest problem is just the consistence of Sanakht's reign: it would surely fit much better before Djoser or perhaps soon after him if we knew that Sanakht reigned few years; archaeological evidence is not very impressive: no tomb or funerary complex has been found and the only massive architecture datable to him is at Beit Khallaf. So I conclude that the Turin Papyrus amount of 19 years is likely a mistake (the same number is also provided for his follower Djoser) and Djoser was effectively either preceeded or directly followed by Sanakht, who reigned only 3-4 years at most. [NdF: the thesis that Sanakht reigned after Sekhemkhet or even after Khaba, although recently embraced by some scholars, is in my opinion far less probable, as explained in Sanakht's page].

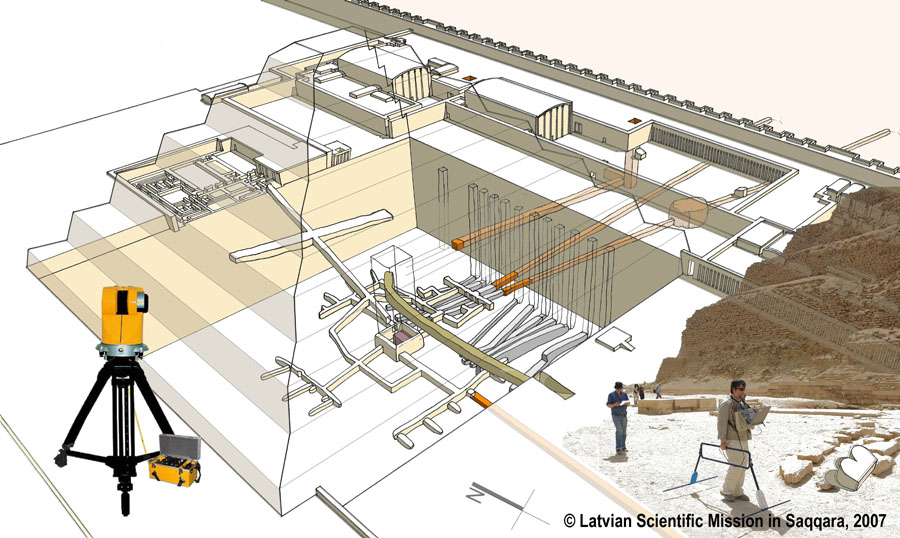

The STEP PYRAMID COMPLEX

It suffices to remark few points: in primis the importance of the excavations that, since 1920s, involved Firth, Quibell, Lauer after that briefer explorations had been lead by Segato, Perring, Brugsch and Lepsius in the century before.2) As far as inscriptional material, the underground chambers and galleries have yielded tens of thousands of vessels, but their importance is almost entirely limited to the study of the immediately previous period (i.e. Dynasty I-II); no example is known with royal names inscriptions of Nebka/Sanakht or Netheryhet/Djoser (cfr. Helck in Z.A.S. 106; Kahl 1994; Lacau-Lauer Pyr.Deg. IV(1959), V(1965)). Actually there is only one bowl bearing the serekh of Horus Netjerykhet (see fig. >).

Other reliefs of Djoser have been found at Horbeit (Shednu, the Lower Eg. XI th nome capital); until recently they were thought of Third Dynasty manufacture, but now they are recognized as Saite copies of Djoser's monuments. From the ruins of a (naiskos) temple at Heliopolis E. Schiapparelli brought back into the Turin Museum, in 1904, about 40 fragments of inscribed white limestone of various size; two women names appear on them: Intkaes and Hotephernebty plus a third one. They are at the feet of the sitting king and rendered in a much smaller scale than the king; they bear the titles of 'King's daughter' (Sat Nswt) and 'King's wife' (Wrt Hts/ Maa Hrw) respectively. A second daughter's name (partly erased) has been read Njankh-Hathor by A.M. Roth (JARCE 30, 1993, 54). The name of the mother (?) NjmaatHapy never appears in these fragments in Turin, most of which (although of minor size) still await a proper publication.

The slab from Horbeit is much similar to another "portrait" (of Djoser ?) from the reliefs found at Tanis (thanks to J.D. Degreef for image and references) [J. Goyon, La découverte des trésors de Tanis, Persea, 1987, 34].

If he was the foundator of the Dynasty, Netjerykhet would be the earliest king whose name was found on the Wadi Maghara reliefs (copper and turquoise mines), where Sekhemkhet, Sanakht and several later kings will also leave incriptions [Gardiner-Peet, 1952, pl. I.2; Weill, Recueils des Inscriptions ..., 1904, 99f.; Kahl et al. 1995, 120f.].

Alike for Sanakht, it seems strange that the two sovereign, maybe brothers, to whom the Turin Papyrus attributes the same regnal duration (19 years), are archaeologically so detatched from each other. The precious Turin Canon reports two lacunary phrases in the row (column III, 5) naming Djoser; the red color for the writing "Nswt Bity" indicates that the original text from which the Royal papyrus was copied (under Ramses II) had this royal name heading a page, column or line.

The Palermo Stone (recto V, 8-12) records the first five regnal years of Djoser (?) (Schafer 1902):

Year I - Appearance of the King of Upper Egypt , Appearance of the King of Lower Egypt; Union of the two lands; Race around the Enclosure Wall.

Year II - Appearance of the King of Upper Egypt , Appearance of the King of Lower Egypt; Passing (ibs) of the Upper Egypt King by the two Snty (Snwty) pillars (or stelae).

Year III - Followers of Horus ; Birth of (a statue) of Min.

Year IV -Appearance of the King of Upper Egypt , Appearance of the King of Lower Egypt; Stretching the ropes for the Qbh Ntrw (foundation of the eastern enclosure).

Year V - Shemsw Hor ; Dj.....(djet feast ?) (cfr. Helck - Thinitenzeit p. 167).Djoser's seal impressions have been found, apart from Beit Khallaf Mastabas K1(16), K2(1), K3(3), K4(1), K5(8), (also ink inscriptions have been found in these tombs, see Kahl et.al 1995), in the Shunet ez Zebib enclosure at Abydos, in the Wadi Maghara (1) in the Saqqara Mastabas of Mereri, in S3518 (1), S 2305 (1) and in S 2405 (1) the latter belonging to Hesyra) and even one in the Step Pyramid of Sekhemhet (Z. Goneim 1957 p. 10 fig. 26), at Hierakonpolis (Quibell-Green, cit., tav. 70,3 & IAF III, fig. 803) and Elephantine (MDAIK 43, 109, fig. 13c, t.15c; J.P. Pätznick, Die Siegelabrollungen ..., 2005).

The 1930s explorations of Djoser's complex burial chamber provided remains of a skeleton: in a typical OK fashion it had been wrapped in linen and covered with plaster so to receive a body-moulding.

Contemporary to Netjeryhet are the masterpieces from the mastaba of Hesyra (see -in italian- here); the carved wooden panels contain features that will be copied for millenia (cheek furrow beside the mouth) and, in the same corridor but on the opposite wall, very deteriorated paintings (only the lower part is but partially visible) depicting the necessary (work tools, games) for the dead; these representations are the first stage in the so called 'daily life scenes' which were going to become so common only few generations after that of the great Netjerykhet.

Unluckily still missing is the tomb of one of the most celebrated and discussed non royal personages of the whole Egyptian history: notwithstanding Emery's excavations in NW sector of North Saqqara élite cemetery, more recent Polish discoveries in the stepped area west of the Complex western wall and two huge mastabas found (late 2007) by a Scottish team lead by I. Mathieson in the North Saqqara cemetery, Imhotep's tomb is still awaiting to come back to light. (Cf. Saqqara page and related bibliography).

How many more years, centuries or millennia are the magic spells in the tomb of of the first sage of human history, protecting his corpse and final abode from the wisdom, skill and luck of modern ages scientists?

General Bibliography

Apart from the books and articles cited in the text, the most important general works are:

(History)

Michel Baud, Djéser et la IIIe Dynastie (Paris, 2002)

Toby A.H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt (London/New York, 1999)

Aidan Dodson, On the Threshold of Glory: The Third Dynasty, KMT 9:2, 1998, 27-40

Nabil Swelim, Some Problems on the History of the Third Dynasty (Alexandria, 1983)

Raymond Weill, La IIe et la IIIe dynasties (Paris, 1908)

W.S. Smith, in: Cambridge Ancient History vol. I/2, (3rd edition) 1971, 145ff.

and, more generally, the chapters in the syntheses of Gardiner (1961), Drioton-Vandier (1962), Vercoutter (1992, p. 245-263).

(Art)

W.S. Smith, A History of Egyptian Sculpture and Painting in the Old Kingdom (Boston, 1949)

J. Vandier, Manuel d'archéologie égyptienne I/2, 1952

H. Sourouzian, in: Kunst des Alten Reiches, SDAIK 28, 1995, 143-154

(Architecture)

J.P. Lauer, Histoire Monumentale des pyramides d'Egypte I. Les pyramides à degrés (Cairo, 1962)

(Inscriptions)

P. Kaplony, Die Inschriften der ägyptischen Frühzeit (Wiesbaden , 1963)

J. Kahl, Das System der ägyptischen Hieroglyphenschrift in der 0.-3. Dynastie (Wiesbaden, 1994)

J. Kahl, N. Kloth, U. Zimmerman, Die Inschriften der 3. Dynastie. Ein Bestandsaufnahme (Wiesbaden, 1995)

W. Helck, Untersuchungen zur Thinitenzeit (Wiesbaden, 1987)INTERNET LINK: http://www.manetho.de/pharao/03dyn/djoser.htm (Ägypten - ein Erlebnis!)

Bet Khallaf, Mastaba K1 (photos and reconstructions by Ottar Vendel): http://www.nemo.nu/ibisportal/0egyptintro/3egypt/beit/index.htm

© FRANCESCO RAFFAELE