|

XVI International

AIDS Conference in Toronto 2006

Aids who it affects 2006

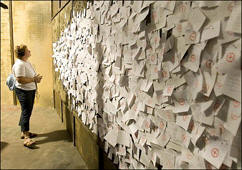

Personal tributes

They are

the names of the dead, neatly handwritten on little white flags.

The 8,000

flags arranged in a field at the south entrance of the Toronto Metro

Convention Centre this week were a personal testament to lives lost to AIDS

each day around the world. It took 40 people and six hours to assemble the

display.

"What we

wanted was to have ordinary folks who care to have their voices heard," said

Lynn Thornton, the executive director of VIDEA, an agency that helped

organize the installation.

Known as

the Community Action on AIDS Project, the Toronto exhibition was one of

eight put up across Canada.

Above the

image of a crying face one caption read: AIDS Doesn't Go Away. Another flag

was simply inscribed: Help.

"Some of

them (are) memories of people who have died, some of them things people

would like to have done here," Thornton said.

Conference

Theme: Time to Deliver - 13/08/2006

The AIDS 2006 Conference theme, Time to Deliver, underscores the continued

urgency in bringing effective HIV prevention and treatment strategies to

communities the world over. Twenty-five years after the first reports of

what was later to be known as AIDS appeared in the CDC’s Mortality and

Morbidity Weekly Report, the magnitude of this epidemic demands increased

accountability from all stakeholders to fulfill their commitments, be they

financial, programmatic or political.

While additional resources and continued scientific research are critical to

an effective global response, the theme recognises that the scientific

knowledge and tools to prevent new infections and prolong life among those

living with HIV/AIDS already exist, even in the poorest settings. The

challenge at hand is to garner the resources and the collective will to

translate that knowledge and experience into broadly available HIV treatment

and prevention programs.

The International AIDS Conference exists for exactly these reasons. It is

one of the most important gatherings for the release and discussion of key

scientific developments in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

AIDS 2006 will bring together the movement of people responding to the

HIV/AIDS epidemic to share their lessons and together stake out the road

ahead. In doing this, the Conference directly affects the lives of those

living with and affected by HIV/AIDS. AIDS 2006 is a catalyst for change.

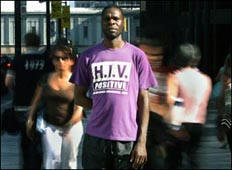

They have

different styles, different backgrounds, and they appeal to vastly

different parts of the population. Yet they have at least one thing in

common: Each seems to have made personal the morale-crushing battle

against the scourge of HIV and AIDS. In the process, they have become

among the world's most influential voices as the lethal disease rages in

its 26th year.

Consider

some of the personalities who have enlisted in the fight: There's Bill

Gates, the world's richest man, and Warren Buffett, his closest rival for

the title. There's movie star Richard Gere, who has proven equally adept

at navigating leading Hollywood roles and symposiums at World Economic

Forum gatherings. (In the 1993 TV movie And The Band Played On,

Gere became one of the first movie stars to openly tackle the subject of

AIDS.)

There's

also the likes of Helene Gayle, a one-time leader of the U.S. Centers for

Disease Control who went on to work alongside Gates as a tireless advocate

for women's rights relating to HIV and AIDS. (At a time in the mid-'80s

when some doctors refused to treat AIDS patients and some hospital staff

would leave meals for AIDS patients on the floor outside their hospital

rooms, Gayle championed AIDS-related research even as colleagues urged her

to avoid involvement because the virus was an "oddball disease" that would

peter out in a few years.)

While

others merit mention — including University of Toronto bioethicist Dr.

Peter Singer and Canadian singer Sarah McLachlan, one of the artists most

active in raising AIDS awareness — much optimism in recent days is

connected one way or another to Gates, who seems to have a hand in causes

ranging from rampant infectious diseases such as AIDS, malaria and

tuberculosis to both first- and third-world education. There's no debating

the fact that Gates, the founder of computer juggernaut Microsoft Corp.,

is doing more in the quest to eradicate the virus that causes AIDS than

anyone else these days. His charity, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation,

last year alone gave away $1.3 billion (U.S.) and has, for better or worse,

bolstered ties to groups like the World Health Organization, the Global

Fund to Fight AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis, and a hodgepodge of the

world's leading medical researchers.

Then

there are the ties Gates seems to have made to former U.S. president Bill

Clinton, who might not have Gates's financial clout but no doubt has an

impressive Rolodex of his own.

Gates has

made a pledge to help finance Clinton's own charity, and the two, together,

will share the podium at this week's XVI International AIDS Conference in

Toronto.

Philanthropy experts contend that Gates's influence goes beyond his

ability to help prop up non-profits. When he contributes to a cause, it

seems be a catalyst to generate more donations.

Says

Harvey Dale, director of the National Center on Philanthropy and the Law

at New York University: "It's like a contribution from Gates is like a

good housekeeping seal of approval."

That

seems to have been the case for Buffett, whose contribution will allow the

Gates Foundation to more than double its annual giving to roughly $3

billion a year.

To be

sure, with Gates and Buffett presenting a united financial front in the

fight against HIV and AIDS, there are still reasons for caution. Some

infectious-disease experts worry that some governments, seeing the

billions committed by the pair, may decide to pare spending related to the

disease.

Nevertheless, as worldwide scrutiny of HIV and AIDS continues to grow —

this week's AIDS conference in Toronto is expected to attract up to 22,000

delegates, more than 10 times the 2,100 scientists who attended the first

such gathering in 1985 in Atlanta — Gates, Buffett, Gayle and others are

taking centre stage in AIDS-related research, using money and moxie,

charisma and connections, to fight the virus.

Ottawa promises

cheap drugs - Health minister decries lack of aid, But current law

prevents action - Aug. 14, 2006

The federal health minister wants Canada to keep its promise of

supplying cheap AIDS drugs to Africa and is seeking advice on

changing legislation that is hindering the flow of life-saving

medication. "If we can put a man on the moon, we can solve this

issue," said Tony Clement of Canada's Access to Medicines Regime,

which, ironically, was designed to boost the Canadian production

of generic drugs for poor countries. The problem, say critics, is

that Canada based its law on an already complicated framework

designed by the World Trade Organization, and muddled it further

when implementing it into national law. To date, not a single pill

has been exported and not a single patient has benefited from the

Canadian law, which was passed two years ago. "Obviously the

legislation isn't working," said Clement, while attending an

international nurses forum in Toronto on the weekend. In the days

leading up to last night's opening in Toronto of AIDS 2006, the

16th international conference on AIDS — the theme of which is

"Time to Deliver" — activists have been extremely critical of

Canada's record. Clement said he has sought advice from

organizations such as Doctors Without Borders and the Canadian

HIV/AIDS Legal Network, as well as Stephen Lewis, the UN's special

envoy for AIDS in Africa, on how to make the law work.

"We

have failed lamentably," said Lewis. "It's almost unbelievable

that two governments — one Liberal and one Conservative — can't

get a single pill to Africa." Lewis said Clement pressed him "fairly

hard" for advice on Saturday on how to get the drugs flowing. The

answer, said Lewis, is to issue compulsory licences to generic

pharmaceutical companies that would allow them to make drugs

without the patent holder's permission. Currently, legislation

stipulates the drug's patent holder and the generic company

planning to reproduce the drug must negotiate at least 30 days

before asking for a compulsory licence. But there is no time limit

on how long talks can last.

"What's

wrong with these governments?" asked Lewis. "In truth, the

minister of health and minister of industry have all the power in

the world to issue a compulsory licence and get the generic drugs

that Canada promised to Africa at prices that Africans can afford

and will save, ultimately, millions of lives."

One of the companies currently caught in the legislation is Apotex

Inc., which has developed the generic Apo-triAvir, but is locked

in negotiations with the patent holder, GlaxoSmithKline.

"This

is not rocket science — a government has great power," said Lewis,

adding that Clement seemed genuinely interested in doing what he

could. But then again, said Lewis, he had a similar conversation

with the minister three months ago and nothing came of it.

Richard Elliott, deputy director of the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal

Network, said he and Doctors Without Borders met three of

Clement's advisers last Thursday.

During the hour-long meeting, both organizations tried to hammer

home the point that Canada needs to introduce a more direct and

streamlined mechanism.

"There

are a number of problems with the (WTO) framework and the Canadian

legislation," said Elliott. "But at its core, it's got the process

backward."

Melinda Gates, in Toronto for AIDS 2006 with her husband to

represent the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, said yesterday

getting drug companies to lower their prices so more drugs can

make it out to impoverished African nations isn't really an issue

any more.

"The issue now is how do we retain enough personnel in these

countries to help administer and deliver the drugs on an ongoing

basis," she told reporters. "And that cost is still very high."

At a press briefing yesterday, Clement said Canada is doubling its

investment in its national fight against AIDS from the current $42.2

million to $84.4 million by 2008. However, this is not new money —

the original announcement was made in December 2005.

Internationally, Canada has committed $800 million in the present

and as for the future, he hinted an announcement could be

forthcoming.

The fight to get a better system to deliver generic HIV drugs

dates back to Aug. 30, 2003, when negotiations among WTO members

resulted in a landmark decision that allowed generic versions of

patented drugs to be copied under compulsory licence and exported

to developing nations.

According to the decision, a generic producer must negotiate a

tentative contract with a developing country to supply a certain

product in a certain quantity at a certain price. Based on that

agreement, the country must send a notification to the WTO

declaring its intention to import drugs and the generic company

must negotiate with the patent holder for a voluntary licence. If

those talks fail, then the generic producer must apply for two

compulsory licences — one in its home country and one in the

country where the drugs are destined if they're protected under

patent there.

"Each

of these steps is time-consuming and holds no guarantee of

success," reads a report by Doctors Without Borders that will be

presented at the conference.

In

September 2003, Canada announced it would implement the WTO's decision and

in May 2004 it passed the Jean Chrétien Pledge to Africa act, which has

since been renamed Canada's Access to Medicines Regime. But it topped its

legislation with additional requirements that made it even tougher for

generic producers to get drugs out.

For

instance, since negotiations over voluntary licensing between generic

companies and patent holders must last at least 30 days, it is tough to

discern when talks are simply stalled or have broken down. Also, the law is

limited to a list of specific medicines in specific formulations. Even if a

generic company makes it through all those hurdles and a compulsory licence

is granted, it is valid for only two years. After that, the entire process

starts again.

At the bare

minimum, said Elliott, Canada needs to get rid of the extra requirements it

added. But that, he warns, would be "sort of like tinkering around the edges"

and not addressing the real problem which is the original Aug. 30, 2003

decision by the WTO to allow copies of patented drugs.

It's

clearly not working, he said, since no one has taken advantage of it. Not

one country has notified the WTO that it plans to import cheaper drugs.

It's an

indication the barriers to accessing the life-saving drugs are simply too

high, said Elliott.

He said he

proposed to Clement's advisers that legislation be enacted that would

automatically grant a compulsory licence to a generic manufacturer.

With that

in hand, the company could negotiate contracts with various countries and

pay royalties to the patent holder based on whatever deals were reached.

Equip women in

fight, Gates urges - Tools needed to prevent HIV infection. Wants leaders,

drug makers to act fast

Bill Gates

wants world leaders and pharmaceutical companies to give women the power to

prevent the spread of HIV by developing drugs that block the transmission of

the virus.

"This could

mark a turning point in the epidemic and we have to make it an urgent

priority," Gates said last night to thunderous applause during his keynote

speech at the opening ceremony of the International AIDS conference at the

Rogers Centre.

"We want to

call on everyone here and around the world to help speed up what we hope

will be the next big breakthrough in the fight against AIDS."

The

Microsoft chairman explained that in many parts of the world, women are at

the mercy of the men in their lives and do not have the right to refuse sex,

let alone sex without a condom.

"No matter

where she lives, who she is, or what she does, a woman should never need her

partner's permission to save her own life," Gates said.

It was a

sentiment echoed by Peter Piot, the executive director of UNAIDS, who said a

"top priority is to immediately double funding for microbicide research and

development."

A

microbicide is a vaginal gel or cream applied prior to sex that will stop

the transmission of HIV, while oral prevention drugs are antiretrovirals

that, taken before infection, may prevent the transmission of HIV.

In a joint

keynote speech, Gates and his wife, Melinda, also called on the audience of

more than 30,000 scientists, advocates and health workers from around the

world to increase global access to HIV prevention and treatment.

"While

there is promising research to report, the world, in my view, has not done

nearly enough to discover these new tools — and I include our foundation in

that assessment," said Gates, referring to the Bill & Melinda Gates

Foundation, which has donated $650 million (U.S.) to the fight against AIDS

— including $500 million just last week.

Last

night's ceremony included speeches by federal Health Minister Tony Clement,

Mayor David Miller, Premier Dalton McGuinty, Governor General Michaële Jean

and conference co-chair Dr. Helene Gayle, as well as musical performances by

Chantal Kreviazuk, Alicia Keys, Barenaked Ladies and Our Lady Peace.

There was

much discussion among them about the simmering controversy over Canada's

failure to get inexpensive generic drugs to poverty-stricken countries in

Africa, as well as the Prime Minister Stephen Harper's absence from the

conference.

Harper's

office has said he could not attend the summit because he is touring Nunavut

in the Arctic.

Comments by

Dr. Mark Wainberg, conference co-chair and director of the McGill University

AIDS Centre, prompted raucous applause and standing ovations from delegates.

"Mr. Harper,

you have made a mistake that puts you on the wrong side of history," said

Wainberg.

"The role

of prime minister includes the responsibility to show leadership on the

world stage. Your absence sends a message that you do not regard HIV/AIDS as

a critical priority. Clearly, all of us here tonight disagree with you."

Money alone 'not enough'

All the

money in the world will not be able to defeat HIV/AIDS unless great strides

are made in preventing new infections — and that can only be achieved by

giving women and other high-risk groups the ability to protect themselves,

Bill and Melinda Gates said on the opening day of the International AIDS

Conference.

At a news

conference Sunday prior to the opening ceremonies, Bill Gates said that

despite growing access to antiretroviral drugs in countries hard-hit by

HIV/AIDS, between four and five million people worldwide will become

infected in the next year.

"I want to

emphasize we're going to have to do a much better job of prevention to stop

the spread of HIV," said Gates, whose foundation just donated $500 million

US to the Global Fund on AIDS. ``We'll never be able to deal with the

numbers of people that would have to go on treatment if we don't make a

dramatic breakthrough in prevention."

The

Microsoft founder said he would call on the world to accelerate research

into microbicides and oral drugs that would prevent acquisition of HIV. "We

hope and expect that this could be the next breakthrough."

Such

measures are particularly important because they would benefit women who now

have to rely on men to agree to abstinence or condom use.

"And that

simply isn't getting the job done," Gates said. "A woman should never need

her partner's permission to save her own life.

"So there's

progress on these but the pace has been too slow."

His wife,

Melinda, stressed the need to use and make more widely available the tools

known to stop the spread of the virus.

"Today

fewer than one in five people who are at high risk for HIV have access to

things like condoms, clean needles, education and testing," she said. "That's

something that simply needs to change

"One of the

things that we fundamentally believe about HIV the more that we've been

involved in this is you have to put the power in the hands of women. That is

going to be the way to change this epidemic."

Bill Gates

and others called on all governments to join the battle against HIV/AIDS

around the world.

"Obviously

the AIDS epidemic is going to require all actors, particularly governments,

to dig deep and make this a high budgetary priority," he said.

"The amount

of money that's required for universal treatment or the things around

prevention far exceed the amount that any individual government, certainly

any foundation, can possibly provide."

Health

Minister Tony Clement agreed that it will take the collective efforts of

people like the Gateses, international advocacy organizations and

governments to wrestle the pandemic to the ground — and the AIDS conference

offers a fresh starting point for that endeavour.

"I can't

imagine another venue, another event around the world that brings together a

more dynamic, a more diverse, a more committed group of people," Clement

said. "We need all of these people — all of their energy, all of their

collective wisdom and all of their passion perhaps most of all.

"I know

that I'll never be able to fully comprehend the absolute devastation that

flows from the human loss associated with this pandemic. But I want you to

know how committed I am and how the government of Canada is committed to

continuing this fight until it is won."

Conference

co-chair Dr. Mark Wainberg, a leading AIDS researcher at McGill University

in Montreal, said "there is no doubt in any of our minds that HIV is the

planet's public enemy number 1. This conference plays such a vital role in

combatting the spread of HIV."

One goal of

the conference is to make sure drugs are available to those who need them

around the world, regardless of ability to pay, he said.

We all

agree. Access to HIV drugs is a right and not a privilege."

But Frika

Chia Iskandar, an HIV-positive woman from Jakarta, told the news conference

that access to treatment is not just about pills — if people don't live

close to medical care, access to treatment also means being able to afford

to get to where the drugs are being dispensed.

As well,

"stigma and discrimination are still happening," she said, noting that a

dentist refused to treat her last year. "It's still there. Nothing much has

changed."

The

conference has brought an estimated 24,000 delegates and 3,000 journalists

from around the world to Toronto for the biggest gathering in the

now-biennial meeting's 21-year history.

Prime

Minister Stephen Harper has said he will not attend the six-day conference

because of other commitments, a decision that has rankled and baffled

organizers, researchers and AIDS activists — not just in Canada but

elsewhere in th world. Instead, Canada is represented by Clement and

Minister of International Co-operation Josee Verner.

Former U.S.

president Bill Clinton, the crown prince and princess of Norway, UN AIDS for

Africa envoy Stephen Lewis, and actors Sandra Oh and Olympia Dukakis are

scheduled to attend.

Conference

workshops and plenary sessions officially begin Monday, and will deal with a

wide range of issues — from scientific research to caring for those with

HIV/AIDS to preventing the spread of the virus, which has killed 25 million

people in the last 25 years and infected about 40 million worldwide.

Virus a weapon in Congo war -

Infected rebels deployed to rape women, children

About

2,000 rebels infected with the deadly HIV virus were conscripted to rape

women and children in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1998-99 in a bid

to spread the lethal virus, a new report alleges.

The

allegations levelled at the African countries of Uganda and Rwanda are

contained in a report written by McMaster University professor Ed Mills

and Johns Hopkins University professor Jean Nachega that is being

circulated at the 16th annual AIDS conference in Toronto.

The

report includes a copy of a complaint filed by Congo's government in 1999

with the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights in the war with

the two countries.

In its

16-page complaint, Congo alleged that "about 2,000 AIDS-suffering or

HIV-positive Ugandan soldiers were sent to the front in the eastern

province of Congo with the mission of raping girls and women so as to

propagate an AIDS pandemic among the local population and, thereby,

decimate it."

Rwanda

and Uganda have each claimed that Congo did not have the right to file a

complaint with the human rights commission.

While

rape has been employed by armies in Africa and elsewhere, this would be

the first instance where soldiers actively tried to spread HIV and AIDS,

Mills said in an interview.

Children

as young as one were raped by the infected solders, Mills said.

"I've

seen war crimes of every possible stripe, but if this is substantiated,

it's a first," said James Orbinski, president and co-founder of aid agency

Dignitas International.

Congo has

been an epicentre for conflict for years. Several non-governmental groups

have said the country has witnessed more deaths due to violence than any

conflict since World War II, mostly through malnutrition. Between 1998 and

2003, some 4 million people lost their lives.

The

United Nations Security Council initially sent troops to Congo, formerly

Zaire, in 1999 to monitor a ceasefire that ended its fight against Uganda,

Rwanda and Burundi.

That UN

deployment was increased in February 2000, but violence has continued in

the West African nation. Mills said the evidence that Ugandan and Rwandan

troops purposefully spread HIV should compel the recently formed African

Court on Human and Peoples' Rights to hear the charges against the two

countries.

African

foreign ministers earlier this year elected judges to preside over the new

human rights court. The court was formed to give victims of war crimes the

chance to seek compensation against governments.

News of

allegations didn't come as a surprise to NGO workers with experience in

sub-Saharan Africa.

Don Kilby,

with the Canada-Africa Community Health Alliance, which supports an

orphanage near the Congo-Ugandan border, said "it's common knowledge over

there that if they don't kill you they can still hurt you by spreading

AIDS and HIV ... so that the country's blood isn't pure any more."

Kilby

said in his group's orphanage, for instance, there's one 4-year-old boy

who was castrated by rebels as an infant.

"They cut

off his penis and testicles, the whole thing so that he wouldn't make any

more Congo babies," Kilby said. "That's the cruelty of war."

Bill and

Melinda Gates opened the conference on Sunday, August 13. Read their

remarks.:

Bill Gates:

Good

evening.

Thank you,

Helene, for that kind introduction, and for everything you’ve done in the

fight against AIDS. Melinda and I are honored to be with all of you here

in Toronto to open the 16th International AIDS Conference.

Melinda

and I have made stopping AIDS the top priority of our foundation. We can

make this commitment — and make it with serious hope of success — because

of the talent and energy of the people here tonight. Whether you are

working to prevent the spread of HIV, caring for people who live with the

disease, or doing scientific research on the virus, we want to say: Thank

you for dedicating your lives to ending AIDS.

Melinda

and I would also like to thank thousands of people around the world who

are an indispensable part of the fight against AIDS. I’m talking about the

people who are participating in clinical trials as we try to find new ways

to treat and prevent HIV. Science can do nothing without their help — and

we want to offer them our deepest thanks and respect.

Tonight,

Melinda and I want to talk about some encouraging signs we see in the

battle against AIDS, and some signs that are more disturbing. But

ultimately, we want to call on everyone here and around the world to help

speed up what we hope will be the next big breakthrough in the fight

against AIDS — the discovery of a microbicide or an oral prevention drug

that can block the transmission of HIV.

This

could mark a turning point in the epidemic, and we have to make it an

urgent priority.

If we can

discover these new preventive tools and deliver them quickly to the

highest-risk populations – we could revolutionize the fight against AIDS.

Melinda

and I returned recently from Africa. We felt a new sense of optimism there

— because the world is doing far more than ever before to fight AIDS. The

Global Fund is active in 131 countries. It gets HIV drugs to more than

half a million people. It provides access to testing and counseling to

nearly 6 million people. It offers basic care to more than half a million

orphans.

The

Global Fund is one of the best and kindest things people have ever done

for one another. It is a fantastic vehicle for scaling up the treatments

and preventive tools we have today — to make sure they reach the people

who need them. That’s why, last week, our foundation announced a $500

million grant to the Global Fund. We’re honored to be a part of their

work.

The

Global Fund is not the only dramatic advance in the world’s efforts

against AIDS. Shortly after the Global Fund’s launch, President Bush

promised $15 billion over five years to fight AIDS, the largest single

pledge ever made to fight a disease. There were a lot of skeptics at the

time, and a lot of them are probably here tonight.

But today,

PEPFAR is supplying antiretroviral drugs to more than half a million

people in 15 countries in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. The President’s

Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief has done a great deal of good, and

President Bush and his team deserve a lot of credit for it.

The

expansion of treatment is making a life-saving difference all around the

world. On our trip to Rwanda last month, Melinda and I went to a clinic,

where they showed us a picture of a thin, sickly man, clearly suffering

from AIDS. I was staring at this picture when a healthy, smiling man

walked into the room and said hello. It took me a minute to realize — it

was the same man.

This is

what treatment is doing for more and more people in the developing world.

We have to build on it — by seeking more funding, creating cheaper drugs

with fewer side effects, and designing more practical diagnostics.

At the

same time, we have to understand that the goal of universal treatment — or

even the more modest goal of significantly increasing the percentage of

people who get treatment — cannot happen unless we dramatically reduce the

rate of new infections.

Between

2003 and 2005, with the infusion of funds from Pepfar and the Global Fund,

the number of people in low and middle income countries receiving

anti-retroviral drugs increased by an average of 450,000 each year. Yet

over the same period, the number of people who became infected with HIV

averaged 4.6 million a year. In other words, for each new person who got

treatment for HIV, more than 10 people became infected. Even during our

greatest advance, we are falling behind.

Let’s

consider what this means for universal treatment. Right now, nearly 40

million people are living with HIV. The lowest price for first-line

treatment drugs is about $130 per person per year; in many cases the cost

is much higher. And the cost of personnel, lab work, and other expenses

easily exceeds another $200 per person per year.

That

means — even when you assume the lowest possible prices — that the annual

cost of getting treatment to everyone in the world who is HIV positive

would be more than $13 billion a year, every year. To put that number in

context, remember that Pepfar — an historic expansion in funding —

designates about $1.5 billion a year for treatment.

This $13

billon figure doesn’t count the cost of much more expensive second-line

therapies, which many patients will need. Moreover, these figures assume

no increase in the number of people living with HIV — yet we’re averaging

4.6 million new infections a year.

We need

to do everything possible to bring down treatment costs, and I’m sure we

will make progress there. But even if you take very optimistic numbers,

when you extrapolate 5 to 10 years, you quickly see that there is no

feasible way to do what morality requires — treat everyone with HIV —

unless we dramatically reduce the number of new infections.

The harsh

mathematics of this epidemic proves that prevention is essential to

expanding treatment. Treatment without prevention is simply unsustainable.

We have

to do a much better job on prevention.

Right now,

one of the most widely practiced approaches to prevention is the ABC

program, for Abstain, Be faithful, use Condoms. This approach has saved

many lives, and we should expand it. But for many at the highest risk for

infection, ABC has its limits.

Abstinence is often not an option for poor women and girls who have no

choice but to marry at an early age. Being faithful will not protect a

woman whose partner is not faithful. And using condoms is not a decision

that a woman can make by herself; it depends on a man.

Another

promising approach is male circumcision. One new study found that it could

significantly reduce the spread of HIV. This is exciting — and if male

circumcision truly is effective, we should make it widely available.

But, like

using condoms, circumcision is a procedure that depends on a man.

That isn’t

good enough.

We need

to put the power to prevent HIV in the hands of women.

We need

tools that will allow women to protect themselves. This is true whether

the woman is a faithful married mother of small children — or a sex worker

trying to scrape out a living in a slum. No matter where she lives, who

she is, or what she does — a woman should never need her partner’s

permission to save her own life.

Let me be

clear: As we discover and distribute preventive tools that women can use

without a man’s cooperation, we are not excusing men from their

obligations to be sexually responsible and to protect their partners. We

are just reducing the consequences to women if they don’t.

In a

moment, Melinda is going to discuss the research underway in microbicides

and oral prevention drugs — products that women could use to protect

themselves from infection.

While

there is promising research to report, the world, in my view, has not done

nearly enough to discover these new tools — and I include our foundation

in that assessment. All of us who care about this issue should have

focused more attention on these tools, funded more research, and worked

harder to overcome the obstacles that make it difficult to run clinical

trials. Now we need to make up for lost time.

We

believe that microbicides and oral prevention drugs could be the next big

breakthrough in the fight against AIDS. We are determined to help medical

science discover these new drugs and get them to the people who need them.

Melinda?

Melinda Gates:

Thank

you. Like Bill, I’m very honored to be here. Compared with so many of you,

Bill and I are relative newcomers to this cause, and we’re deeply inspired

by those of you who long ago committed your lives to ending AIDS.

When it

comes to stopping this disease, there is no silver bullet. We need to be

much more aggressive about getting all of today’s prevention tools to

everyone who needs them. And we need a constant stream of new innovations

— especially those that put the power to prevent HIV in the hands of women.

Of course,

the most highly anticipated milestone on this path is a vaccine. It’s a

major focus of our foundation, and we’re intensifying our efforts in this

area. Last month, we announced a series of grants to help develop and

evaluate vaccine candidates. These grants support the priorities that were

identified by the Global HIV Vaccine Enterprise, an alliance of

researchers, funders, advocates, and private industry that is dedicated to

speeding up the development of a vaccine.

But

finding an HIV vaccine is a long-term project. That’s why we have to

accelerate research on other preventive tools that can be available sooner.

As Bill

said, we believe the most promising breakthrough that could be available

soon is an effective microbicide or oral prevention drug.

Microbicides are gels or creams that women can use to block infection.

They’re the first preventive tools that would be intended specifically for

women’s use. Sixteen candidate microbicides are now being clinically

evaluated. Of those 16, five are in major advanced studies.

Another promising approach is an oral prevention drug. The hope behind

this research, as you all know, is that the anti-retroviral drugs that are

now used for treatment might also be effective for prevention.

Antiretroviral drugs have already been proven to lower the risk of

infection for babies born to infected mothers. Some have been successful

in preventing HIV infection in animals.

Drug trials are planned or underway in Peru, Botswana,

Thailand, and the United States. These studies are promising, but we need

more trials of more candidates in more places — for both microbicides and

oral prevention drugs — if we’re going to stop the spread of HIV.

The discovery of effective microbicides or an oral prevention pill is a

very exciting prospect. Bill and I are making it an immediate priority for

our foundation. But no discovery can save lives unless we distribute it to

everyone who needs it, and the record so far suggests we’ve got a lot of

work ahead of us.

Today,

fewer than one in five of the people at greatest risk of HIV infection

have access to proven approaches like condoms, clean needles, education,

and testing. That’s a big reason why we have more than 4 million new

infections every year.

Why aren’t

we getting these life-saving tools to the people who need them?

There are

many reasons — financial, logistical, political, social. But there is one

reason I want to emphasize today, and that is stigma.

The

simple fact is that HIV is transmitted through activities that society

finds difficult to discuss — activities that are infused with stigma — and

that stigma has made AIDS much harder to fight..

The image

of stigma was burned into my mind during a visit Bill and I made last

December to an AIDS hospice in South India. The patients in the hospice

were separated by gender. The long narrow trailer of the male ward was

filled with families and flowers. Children came to spend precious last

minutes with their fathers.

Across a

courtyard, we saw a very different scene. The female ward was a lonely,

desolate place. There were no visitors — just women wasting away from

AIDS. Some of them had managed to get themselves to the hospice; others

had been abandoned there by a relative who no longer wanted anything to do

with them. There was no love, no warmth, no comfort. Just wives and

mothers, left alone to die.

Stigma is

cruel. It is also irrational.

Stigma

makes it easier for political leaders to stand in the way of saving lives.

In some countries with widespread AIDS epidemics, leaders have declared

the distribution of condoms immoral, ineffective, or both. Some have

argued that condoms do not protect against HIV, but in fact help spread

it.

This is a

serious obstacle to ending AIDS. In the fight against AIDS, condoms save

lives. If you oppose the distribution of condoms, something is more

important to you than saving lives.

Some

people believe that condoms encourage sexual activity, so they want to

make them less available. But withholding condoms does not mean fewer

people have sex; it means fewer people have safe sex, and more people die.

When Bill

and I visit other countries, we are enthusiastically accompanied by

government officials on all our stops... until we go meet with sex workers.

At that point, it can become too politically difficult to stay with us,

and sometimes our official hosts leave.

That is

senseless. People involved in sex work are crucial allies in the fight to

end AIDS. We should be reaching out to them, enlisting them in our efforts,

helping them protect themselves from infection, and keeping them from

passing the virus along to others.

If

politicians need a more sympathetic image to make the point, they should

think about saving the life of a faithful mother of four children whose

husband visits sex workers. If a sex worker insists that her clients use

condoms, that sex worker is helping to save the life of the mother of

those children.

If you’re

turning your back on sex workers, you’re turning your back on the faithful

mother of four.

Let’s not

turn our back on anyone. Let’s agree that every life has equal worth and

saving lives is the highest ethical act. If we accept this, then science

and evidence — untainted by stigma — can guide us in saving the greatest

number of lives.

This is

the only way we will get the full life-saving power of the preventive

tools we have today and the ones we’re going to discover tomorrow.

If we’re

going to make dramatic advances in prevention, no one can go it alone. We

all have a role to play.

We at the

Gates Foundation will keep investing in research on microbicides and other

preventive tools. We will also do everything we can to remove the

roadblocks that stand in the way of trials.

I hope

AIDS activists will use their influence to push for more research into

prevention and to insist that we bring the tools we already have to the

people who need them. Nobody has the power you have to focus attention,

apply pressure, and get action.

You

proved this when you pushed for new treatment; the world now needs you to

push just as hard for prevention.

Governments should make the search for new prevention tools, such as

microbicides, a bigger priority in their budgets. If they can, they should

host clinical trials, and use their influence to help the trials run

smoothly.

Pharmaceutical companies can make a powerful contribution by spending more

on research and development for preventive tools, including microbicides.

But there is another exciting way in which they can contribute. Drug

companies have developed medicines to treat people with HIV. They should

do more to share these drugs with researchers who want to test whether

they can also be effective for prevention.

Researchers can help test the drugs more quickly by developing novel trial

designs, finding faster ways to analyze data, and coming up with

biomarkers that can help test a hypothesis without needing a clinical

trial of 10,000 patients. They should also make sure that when clinical

trials are run, they benefit those who are in greatest need.

The WHO,

UNAIDS, and other organizations should help develop common ethical

standards for clinical trials so they can start faster and run without

interruption.

If all

these players do their part, we will move forward, as fast as science can

take us, to discoveries that can help block the transmission of HIV. This

goal is worth our greatest efforts; it could very well be the turning

point that leads to the end of this disease.

In

closing, I want to say how deeply inspired Bill and I are to see so many

people gathered together here committed to this great cause. It is hard to

overstate the historic scale of our goal. In the history of human

accomplishment, ending AIDS will fill a category all its own. It will

stand as a work of scientific genius. It will be a testament to diplomatic

brilliance. It will represent enormous generosity of spirit and compassion.

But above

all — and unlike so many other great works — ending AIDS will not be the

success of one great scientist, one great community worker, or one great

leader; it will be an accomplishment of the whole human family working

together for one another. Thank you, once again, for dedicating your lives

to ending AIDS. We’re so honored to be part of your work.

Thank you.

Grandmothers going global - Aug. 14,

2006

The

Grandmothers to Grandmothers gathering has all the markings of

becoming a truly international movement.

Stars

such as U.S. Grammy winner Alicia Keys and actress Olympia Dukakis,

along with British pop singer Elton John, are throwing their weight

behind the cause of African grandmothers who have lost their children

to HIV/AIDS and now raise orphaned grandchildren.

As

ceremonies ended yesterday for the three-day grandmothers' gathering

in Toronto, the African grandmothers continued their joyous expression

of love and faith, singing, chanting and dancing.

But,

for UN Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS Stephen Lewis, it's just the

beginning. Lewis told the Toronto Star that the Stephen

Lewis Foundation has begun discussions with Keys and John to make the

movement a truly international one. Both stars have their own

charities involving HIV/AIDS and have expressed interest in helping to

get grandmothers from around the world involved.

"There

is a kernel here of something much bigger than itself," said Lewis

after the closing of the conference. "It seems we have the means of

lifting it off the ground and making it an international cause

célèbre."

Lewis's daughter, Ilana Landsberg-Lewis, who runs his foundation, came

up with the idea of bringing the grandmothers together. The Lewis

foundation funds HIV/AIDS programs in Africa.

Canadian grandmothers were asked to raise money to help their African

counterparts. What was to be a modest gathering of the Canadian and

African grandmothers just before the International AIDS Conference

took off and culminated with their message being beamed around the

world.

International news media — including CNN, the South African

Broadcasting Corporation and the BBC — jockeyed for space with local

media covering the closing session and a walk through Toronto's

downtown.

Early

yesterday morning the 300 grandmothers, bearing banners and signs that

called for an end to HIV/AIDS, were joined by singer Keys as they

marched and sang until they arrived in the atrium of the CBC Broadcast

Centre on Front St. Then Keys, hand in hand with Lewis and with an arm

wrapped around a Kenyan grandmother, ushered the women inside.

"I'm

honoured to be here marching with you," she said. "I feel like the

silence has been broken."

Keys

told the crowd she loves her own grandmother deeply and can't imagine

her losing her children and having to raise grandchildren. Keys didn't

perform but did join the grandmothers in a rendition of We Shall

Overcome. A videotaped message from Elton John was also played.

The

grandmothers presented a statement to Dr. Mark Wainberg, co-chair of

the International AIDS Conference, calling for more food, housing,

clothing and education for the African grandchildren. They also asked

for education and training for African grandmothers who feel

ill-equipped to raise children who are bereaved, impoverished,

confused and vulnerable.

The

recommendations also called for global action — including a pledge by

Canadian grandmothers to not only mobilize funds but also "apply

pressure on governments, on religious leaders and on the international

community."

"We

grandmothers deserve hope," Joyce Gichuna, a Kenyan grandmother, told

the crowd. "Our children, like all children, deserve a future. We will

not raise children for the grave."

Wainberg used the opportunity to deliver a scathing attack on Prime

Minister Stephen Harper. The Prime Minister has chosen not to attend

the AIDS Conference.

"I

don't understand why Mr. Harper fails to understand that HIV is the

world's public enemy No. 1 ... And why, given that HIV is the most

important enemy on this planet, is Prime Minister Harper not here to

show leadership on the world stage? As a Canadian it breaks my heart."

The

same can't be said for grandmothers attending the conference. Their

hearts were soaring as they headed home with a renewed sense of hope.

"I'm sure the world will now recognize the plight old people have been

through because of the pandemic," said South African grandmother

Princess Ntombenhle Mkhize.

"They

want the same thing we want for our grandchildren — a brighter

future," added Canadian grandmother Gisele Lalonde Mansfield, who lost

her brother to AIDS and is climbing Kilimanjaro next year in his

honour.

Clinton,

Gates urge more AIDS testing - Aug. 14, 2006

The

urgent need to stem the tide of new HIV infections is being undermined

by the fact too few people know their HIV status and are unwittingly

spreading the disease, former U.S. President Bill Clinton warned today

as he took the stage with Microsoft founder Bill Gates at the

International AIDS Conference.

“I

don’t see how we’re ever going to catch up, unless people are at least

aware that they could be giving the virus to other people,” Clinton

told a huge audience, drawn by the chance to listen to two of the

world’s most influential men — both committed warriors in the fight

against HIV/AIDS — expound on the issue in a panel jokingly referred

to as the double-Bill.

“We’re still behind the eight ball. And I think we’ve got to continue

to fight stigma and got to stop people . . . from being afraid of

being tested.”

Ninety per cent of HIV-infected people in developing countries don’t

know they carry the virus, Clinton noted.

In

many settings, people known to be HIV-positive are still ostracized.

And in places where there is no or limited access to life-saving

antiretroviral drugs, there may be little incentive to finding out

whether one is infected with the virus that causes AIDS.

The

scale up of programs to deliver badly needed AIDS drugs to developing

countries could start to chip away at that problem, Gates noted,

adding that having treatment broadly available “does start to change

the dialogue.”

But

cracking the nut of stigma will be difficult, suggested Gates, who

noted that in his travels to afflicted countries around the globe,

having a discussion with officials about the behaviours that fuel the

spread of the virus — unprotected sex and injection drug use — is

invariably an awkward encounter.

“I

haven’t come to a country where injecting drug use is easily discussed

or men having sex with men or commercial sex workers,” Gates said to

laughter and applause.

“I

hope to go to that country some day, where none of those things are

controversial or hard to discuss. But we don’t really have that.”

The

fight against AIDS has always been complicated by the way the virus is

spread, with moral and religious beliefs colouring responses on some

fronts. While public health experts cite sound evidence that needle

exchange programs and condom distribution save lives, some — including

the current U.S. administration — prefer to stress abstinence and

monogamy.

While

neither man overtly criticized that approach, they did suggest

over-emphasizing abstinence was ignoring the reality of human

behaviours.

“An

abstinence-only program is going to fail. And in the end you’re going

to wind up being in a cruel fix,” said Clinton.

The

session began with a minor demonstration, with a number of members of

the audience drowning out the moderator to demand affluent countries

stop poaching health-care workers from developing countries, a

practice that has left some of the world’s poorest countries bereft of

doctors and nurses.

“We

need more nurses,” the protesters chanted.

“I

actually agree with that,” Clinton said, taking the wind out of the

disruption. “We do need a lot more nurses.”

The

former president did not agree, however, to a request from the crowd

that he consider becoming Canada’s prime minister — a dig from an

audience member, perhaps, at Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who has

refused to attend the conference.

Clinton side-stepped the potentially awkward moment by

noting that he has been in Canada so often since ending his presidency

that he should check with his accountant to see if he ought to pay

Canadian taxes.

New HIV drug appears to be 'very

potent'

TORONTO

-- Patients taking a brand new type of HIV drug have shown a quick reduction

in the number of viruses circulating in their bloodstream, according to

early data from a clinical trial that is to be announced at the

International AIDS Conference in Toronto later this week.

The drug

belongs to a long-awaited new class of HIV medications known as integrase

inhibitors. They work to block the enzyme the virus uses to integrate its

genetic material into the DNA of a host's cell and make copies of itself.

As more and

more patients develop drug resistance to standard therapies, integrase

inhibitors are raising hopes of a new first-line treatment against the AIDS

virus.

"For people

with resistance to many different drugs, this [early study data] offers them

hope," said Martin Markowitz, one of the trial's investigators and a

clinical director at the Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center in New York.

But Dr.

Markowitz, who is also a professor at Rockefeller University, cautioned that

"it is too early to predict where this will lead."

Merck & Co.

is developing the drug, one of two in the new class. Its compound, known for

now as MK-0518, is involved in an ongoing clinical trial with 198 HIV

patients who had previously been untreated for their infection. The studies

are being conducted at 28 different centres around the world, including two

in Canada.

At the

outset, the patients had to have at least 5,000 copies of the virus in every

millilitre of blood. They also had relatively low counts of the immune

system's CD4 cells, which HIV attacks. Cell counts averaged between 271 and

314 per microlitre.

(Treatment

usually begins when a patient has more than 100,000 copies of the virus or

below 350 CD4 cells). Most of the patients in the trial, 160, were given the

new oral drug in combination with two other antiretroviral therapies.

Thirty-eight were given an existing type of HIV medication as well as the

two other antiretroviral agents.

Based on

data at six months into the two-year trial, Merck reports that 85 to 95 per

cent of patients taking the integrase inhibitor drug regimen have seen their

viral loads plummet to less than 50 copies.

Patients'

immune-cell counts, meanwhile, increased by 139 to 175. Ninety-two per cent

of patients taking the older drug combination showed similar results, but

the effect took longer to achieve.

"What is

striking is the rapidity with which the patients reached these lower levels

[of viral load]," Dr. Markowitz said. "This looks to be a very potent drug."

The drug's

antiviral effect was seen in patients taking the oral drug at doses ranging

from 100 milligrams to 600 milligrams twice a day.

A press

release from Merck states that side effects in the trial have so far been "mild

to moderate, with nausea, dizziness and headache reported most frequently."

Dr.

Markowitz noted that 10 patients have discontinued taking the medication,

two for lack of efficacy, seven for reasons not related to the trial and one

because of an adverse effect related to liver function.

Mark

Wainberg, director of the McGill University AIDS Center and co-host of the

Toronto conference, said the results sound encouraging.

What's

more, Dr. Wainberg stressed, the research field desperately needs good news:

"It's pretty urgent. People are still dying of AIDS because they are

resistant to everything we have to treat them."

Researchers

have found integrase inhibitors difficult to develop in part because it

requires altering the viral genome without harming the DNA of the host. Dr.

Markowitz said it is satisfying to finally see the new drug class move into

clinical trials.

"We have

drugs that target two of three enzymes that HIV requires for its life cycle,"

he said. "This is like the third leg of the stool."

Tiny grants, big hope in AIDS

fight

In the

Mashuru area of Kenya, a single woman with HIV who had no source of income

now runs a small general store, is self-sufficient and, most importantly, is

eating properly, thanks to a $140 grant from World Vision.

In the same

region, a group of 15 women have used a $1,400 grant from the humanitarian

organization to expand a small business of rearing goats for sale at market,

using the added profit to care for HIV orphans and vulnerable children in

their village.

“What's

really crucial is to empower women to have a say in their lives so they can

become less vulnerable,” said Carole Leacock, a HIV/AIDS program specialist

with World Vision Canada, who noted that women in rural villages tend to be

more stable, while men often travel to get work.

Unlike big

business grants, injections of small amounts of money in Third World

countries can play a critical role in developing a thriving local economy.

That's

especially true in areas where disease has devastated households, creating a

situation that perpetuates poverty and undermines the community safety net

with people unable to care for themselves.

Ms. Leacock

gave an audience at the International AIDS Conference in Toronto yesterday

the results of a microfinance project in Mashuru, located about 120

kilometres southeast of Nairobi, where droughts in recent years have made

people living with HIV and AIDS destitute.

Forty-seven

microfinance projects last year gave people living with HIV and AIDS basic

business training that improved their disposable income, health, nutrition,

dignity and self-respect, as well as better access to anti-retroviral drugs,

and decreased the stigma of the disease, she said.

“No one is

going to bed hungry they were able to repair their houses, pay rents, create

assets and send their children to school. Today, they continue to be engaged

in gainful employment as small trades by reinvesting their savings.”

Ms. Leacock

also said people can now afford the $3 bus trip for a 50-kilometre monthly

visit to the nearest health facility that dispenses free anti-retroviral

drugs.

“Every time

we make a difference in one parent's life, we prevent another child from

become orphaned. And that's very important to us.”

Results of

another World Vision microfinance project in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, will be

released at the conference tomorrow.

Dina

Eguigure, a national manager of HIV/AIDS programs in Honduras, said that

results of a two-year project found that helping people with the disease set

up their own businesses increased “social inclusion of a group normally

excluded from the formal economy.”

Nearly

$50,000 (U.S.) was earmarked to help 150 families living with HIV, with 37

per cent of the money used by women with no formal education. Most women set

up small businesses attached to their homes, selling traditional foods,

small goods and second-hand clothes purchased elsewhere, she said.

“By the end

of the project, they paid up their credits with no outstanding debts,

showing their business skills and the solid coaching provided by the project

team.”

Largely

designed to improve the quality of life for adolescent women between 15 and

19 years of age and mothers living with HIV and AIDS, the project also

trained teachers and youth leaders about sexual and reproductive health, HIV

prevention and proper use of anti-retroviral treatments. It also

strengthened community grassroots organizations and helped develop stronger

government links, she said.

A place for medical marijuana

Nestled

in a corner of the AIDS conference's Global Village is a group of

individuals trying to raise awareness about the therapeutic benefits of

using cannabis to treat AIDS symptoms.

"It's a

serious crime that this plant is illegal in most countries," said Hilary

Black, a spokeswoman for the Medical Marijuana Information Resource

Centre.

In

Canada, which is the only other country aside from the Netherlands that

hands out licences authorizing the possession of medical marijuana to

people living with HIV-AIDS, only a quarter of those infected are

smoking the drug legally.

"The

information really needs to be out there because cannabis is saving

lives," Ms. Black said, adding that there is clinical evidence showing

that smoking it can alleviate nausea, increase appetite, and increase

adherence to HIV-AIDS medication.

This is

the first time medical marijuana has been represented at the

International AIDS Conference and the information booth has been a hit,

Ms. Black said.

"It's

actually being talked about professionally, rather than being giggled

about or talked about in the closet."

Hitting

the road for the cause

Princess Kasune Zulu's radiant smile and big eyes hide well the pain and

suffering she has seen in her 30 years.

After

losing her baby sister, older brother and both her parents to AIDS as a

teenager, the young Zambian couldn't deal with the pressures of heading

a household full of siblings and cousins looking to her as their only

hope.

She

dropped out of school and had a baby girl by 18, married her boyfriend

25 years her senior and had a second daughter right before they divorced.

But the

real blow came when she tested positive for HIV at 21.

"I was

not traumatized but rather filled with overwhelming peace," she said

yesterday. "My diagnosis was a spiritual awakening."

She

decided to hit the road with her status, against the wishes of the

church and her ex-husband. She dressed up as a "commissioned sex worker,"

walked along the highways of Zambia and hitchhiked with truck drivers.

Her intent was to tell them about the spread of HIV and her own

diagnosis because truck drivers were known to sleep with dozens of young

sex workers and be a conduit for infection.

"I knew

I had to reach the adult men and tell them what they were doing because

those young girls, you can't just tell them to stop. Those girls [were]

doing it to raise school fees, or buy their younger brothers and sisters

shoes to wear to school, sneaking out at night while their grandmother

is asleep."

Ms.

Zulu's story has been heard by presidents and heads of state around the

world. She is currently working on her book, I Will Not Die Before I'm

Dead: A Memoir of Hope in the World of AIDS, which will be released

next year

Four-drug cocktail no better,

study finds

TORONTO

-- Adding a fourth drug to the current triple-drug cocktail is no better at

treating newly diagnosed patients with HIV, according to a study released at

the International AIDS Conference yesterday.

The study,

published in the Aug. 16 issue of the Journal of the American Medical

Association, found that adding a fourth HIV drug, in this case abacavir, did

not reduce the amount of virus in patients' blood. Previous smaller studies

had been contradictory on the matter; some suggested that adding a fourth

drug could more quickly beat back the virus, while other studies did not.

This study,

which followed 765 patients over three years, found that in roughly 80 per

cent of the subjects, the human immunodeficiency virus remained suppressed

whether they were on the three- or four-drug cocktail, according to the

results released by Roy Gulick, director of the Cornell University HIV

clinical trials unit and associate professor of medicine at Weill Medical

College of Cornell in New York.

"It doesn't

look like adding a fourth drug to the very successful three-drug regimen

taken today provides any additional benefit," he said at a morning news

conference.

In the

study, 765 HIV-infected patients who had never received treatment were

randomly assigned to one of two regimens: a four-drug cocktail that included

zidovudine, lamivudine, abacavir and the non-nucleoside drug efavirenz; or a

three-drug cocktail of zidovudine, lamivudine and efavirenz.

According

to Dr. Gulick, the rationale for the study was predicated on past success:

Since the triple-drug cocktail worked better on HIV patients than the

two-drug cocktail, researchers wanted to learn whether four drugs would be

better.

In the

study, which ran from 2001 to 2005, roughly the same number of patients in

each group (88 per cent in the four-drug group and 85 per cent in the

three-drug group) achieved undetectable levels of virus in their blood.

After three years, 25 per cent of the four-drug group and 26 per cent of the

three-drug group achieved so-called virologic failure, which meant that the

drugs were no longer effective at reducing the levels of virus in their

blood, according to the study, which was supported by grants from the U.S.

National Institutes of Health.

The Aug. 16

JAMA issue was published to coincide with the AIDS conference; its contents

are devoted entirely to HIV/AIDS. Another study in the issue found that

rapid expansion of free anti-retroviral therapy programs in Zambia produced

favourable outcomes.

At the news

conference yesterday, JAMA editor-in-chief Catherine DeAngelis said the AIDS

epidemic now matches the deaths from the bubonic plague.

About 25

million people have died of HIV/AIDS in 25 years and about 40 million people

currently have it. Anti-retroviral medications have turned HIV/AIDS, once a

death sentence, into what many consider a chronic disease.

Simple solutions to save

newborns

There was

lots of buzz, at the opening of the 16th International AIDS Conference

yesterday, about the new: new drugs; new technologies; new deals on funding

and drug access.

Far away

from the buzz, clinicians from the developing world talked about keeping

pregnant women from passing the AIDS virus on to their babies.

There is

nothing new about this: We've known how to do it for nearly a decade. It's

cheap, and it's one surefire way of cutting down on new infections. And?

More than 90 per cent of pregnant women with HIV around the world do not

have access to any of the simple interventions that would keep them from

infecting their babies. Seventy children an hour are infected with the virus

by their mothers, and 45 die every hour from AIDS.

These

numbers suggest that in all the understandable hunger for the new in AIDS,

we have lost sight of the fact that we haven't yet figured out how to solve

one of the most basic problems. And because this is a problem of women --

poor, rural women in Africa, in particular -- it has slid quietly to the

bottom of the international AIDS agenda.

Women

infect their babies with HIV three ways: roughly a third of them in utero; a

third in delivery; and a third through breastfeeding.

Fewer than

500 children will be infected in North America this year, because it's very

easy to prevent all three. If a woman doesn't breastfeed, if she delivers by

cesarean and if she and her baby are given an anti-retroviral drug before or

during labour, the risk of transmission is less than 2 per cent.

Of course,

not every rural health clinic in Rwanda can provide a cesarean section. And

not every Rwandan woman can feed her baby with formula safely, because many

lack clean water. But the drug intervention -- that's easy. A single dose of

the drug nevirapine can cut transmission by at least 30 per cent. That costs,

at most, a couple of dollars, and manufacturer Boehringer Ingelheim donates

it free in many parts of the world. Using two or three ARV drugs together

can lower transmission by much more. But less than 9 per cent of pregnant

women worldwide get any of these interventions.

African and

Indian doctors talked about how they lack the labs and the staff to test and

counsel all the pregnant women; how the women they see may come for an HIV

test but never return for drugs because they live too far away and can't

afford to take another day off work to wait in line at a busy clinic.

Dr. Agnes

Binagwaho, who heads the national AIDS agency of Rwanda, talked about her

country's program, which is, by African standards, a remarkable success:

They're reaching 22 per cent of HIV-positive pregnant women with single-dose

nevirapine. But that program is now imperilled. "We had funding from the

Global Fund," she said, money they used to build labs and train and pay

staff. "But that funding ends now."

Arletty

Pinel, of the UN Population Fund, says the fact that more women don't get

this service reflects the overall low priority put on maternal and

reproductive health. These programs are almost universally minimally funded

and minimally staffed, she said, and so it's no surprise that more women

with HIV don't get the basic interventions. "Getting a pregnant women who is

HIV positive is remedial, it's damage control -- and we don't do damage

control well."

The World

Health Organization announced yesterday that it now recommends putting

pregnant women with AIDS on full ARV therapy from 28 weeks of pregnancy. A

fine idea, but if less than 9 per cent of women are receiving a one-off drug

dose, how on earth are Rwandan clinics that just lost their funding going to

do full therapy?

One of the

big topics at the conference this week is pediatric AIDS. It's high time

that pediatrics got more attention. But in all those sessions yesterday, no

one mentioned that there would be no need for pediatric treatment, if we

just mastered the one-stop intervention that keeps mothers from infecting

their kids

Prevention tools for women

urged

Toronto

— Women's issues were front and centre Monday at the International AIDS

Conference as Melinda Gates called for prevention tools for women so they

don't become infected by HIV.

“The two

that are on the horizon that I think really could change the face of this

disease are a microbicide, which is an odourless clear gel that a woman

would use vaginally to block the disease, or an oral prevention drug that a

women could take every day without her partner knowing,” she told a panel

discussion entitled Women at the Frontline in the AIDS Response.

But money

isn't the only obstacle in bringing these products to market, and making

them accessible to women in developing countries who can't protect

themselves against infected partners who don't use condoms.

“It really

comes down to trials,” said Ms. Gates, who together with her husband

Microsoft chairman Bill Gates gave a keynote address to open the conference,

and recently announced $500 million (U.S.) in funding to the Global Fund to

Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

“We have 16

microbicide candidates today that are in first-stage trials, we have five

that are on their way to second-stage trials, but the truth is we need an

even more powerful microbicide than what's in trial today,” Melinda Gates

said.

“And a lot

of trials, both in microbicides and an oral prevention drug — in some ways

what's even more promising — have been stopped. And so we need to have more

trial sites created. We need more communities involved. We need more people

willing to come forward to participate in trials.”

Activists

need to make sure trials are ethical and done according to best clinical

practice methods, she said. But they also need to insist that trials be done.

Musa (Queen)

Njoko, a jazz artist and HIV activist in her native South Africa, was also

on the panel. She was one of the first women and the first recording artist

to disclose her HIV-positive status in South Africa.

“We need no

longer continue having our lives controlled by other people,” she said.

“It's our time, it's our lives, let's fight for our survival, let us fight

for the future of our children.”

Earlier

Monday, more than a thousand people from around the world took part in a

march and rally near the conference site to demand urgent action for women

and girls in the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

“Violations

of women's and girls' human rights have a direct impact on HIV infection,”

Louise Binder, co-founder of the Blueprint for Action on Women and Girls and

HIV-AIDS, said in a statement.

“Violence

against women and girls, poverty, lack of education and housing, and lack of

property rights, all fuel HIV/AIDS infection rates among women and girls.

HIV positive women's human rights are also regularly violated.”

Worldwide,

almost 50 per cent of all HIV positive adults are women over 15 years old.

In Canada,

women represented 27 per cent of positive HIV tests in 2005.

Unique

tribe of activists stands ready to shame the negligent and the greedy

- Aug. 15, 2006

These

are some of the tools AIDS activists like Paul Davis use to fight the

lethal virus: fake blood and banners, padlocked lengths of chain, foam

sculptures — and this week, maybe even a few funeral urns.

It's

a far cry from the orthodox measures employed in the high-stakes

medical battle. While infectious-disease researchers, politicians and

aid agencies this week discuss advances in protease inhibitors or safe

needle exchange programs, Davis and about 1,000 other activists have

flocked to Toronto to protest allegedly greed-fuelled drug companies

and idle politicians.

With

22,000 delegates and 8,000 journalists, exhibitors, volunteers and

staff at the mammoth International AIDS Conference, there is no better

opportunity to spotlight their gripes.

"We're

trying to capture the imagination of the public and provoke a response

from decision-makers," said Davis, who has worked with the group Act

Up Philadelphia for 13 years.

For

the past few days, dozens of activists have been stationed at the

University of Toronto, formulating plans behind closed doors and

conducting informal sessions for nascent protestors on how to interact

with reporters.

Yesterday, activists held a small protest at the Metro Toronto

Convention Centre. But they pledge more to come.

At

past conferences, protestors have held mock trials for world leaders

and staged "die-ins," zipping themselves into body bags, or "chain-ins,"

chaining themselves to fixed objects.

"A

lot of what we do is street theatre," said Eric Sawyer, a New Yorker

who has helped launch three AIDS groups. "We basically won't do