|

|

|

|

Horus KHABA

The serie of stone bowls of Khaba represent a return to the past tradition which had ended with Khasekhemwy; in Djoser's Step Pyramid complex no inscription of Khaba was found on Stone vessels; after Khaba the trend to produce and inscribe stone vessels was abandoned again to be reprised only during the reign of Snofru.

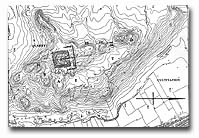

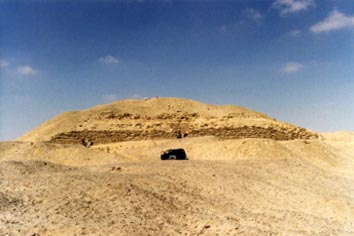

The Layer Pyramid, 1,5 Km south of the other unfinished

pyramid of Zawiyet el Aryan, was superficially visited by Perring, Lepsius,

Maspero and finally de Morgan in the end of '800; it was explored for

the first time also in its subterranean part by the Italian archaeologist

Alessandro Barsanti in 1900 (A.S.A.E. 2 p.92-4). He began the excavation

on March, 11, starting to clear the east-west descending entrance passageway

which de Morgan had found in 1896. In 1910-11 the Boston Museum of Fine

Arts expedition directed by G.A. Reisner with C. Fisher reenvestigated

the site; they were the first ones to attribute the Pyramid to King Khaba

on the basis of the inscribed bowls with red ink name they found in the

Z500 tomb, c. 200 m north of the pyramid; indeed the American archaeologist

proposed, years later (Tomb Development 1936, p. 134), a higher datation

to an unknown II nd dyn. king, mantaining that the underground labyrinths

(always in comb-like plan) were a late effort by saitic pharaohs (keep

in mind that the similar galleries under the pyramid of Sekhemhet had

not yet been discovered at that time).

When, in 1963, the Italian Vito Maragioglio and Celeste Rinaldi published

the second volume of their massive and very useful study 'L' Architettura

delle Piramidi Menfite' (p.41-9), it was noted for the first time that

there were very deep incongruities in comparing the drawings of Barsanti

with those of Reisner-Fisher.

In 1978 appeared a volume of the then 87 years old Dows Dunham dealing

with part of the c.300 graves of Zawiyet el Aryan;.

the author re-published Reisner-Fisher's map of the Layer pyramid (which

has always been more credited than Barsanti' s) and provided some of the

BMFA unpublished drawings and photos; most of the tombs are Late predynastic

and early Ist Dynasty (serekh of Horus Aha in Z.2 and of Narmer in Z.401).

Dunham (Zawiyet el-Aryan - The Cemeteries adiacent to the Layer Pyramid

p.29) states that Mastaba Z.500 had a east-west orientation: perhaps he

misinterpreted a sketch by C. Fisher (Lehner,1996 fig. 2) which probably

represented the eastern part of the pyramid's east-west entrance. As recently

precised by Lehner (see below) Z500 has a north-south major axis.

In his thesis on the History of the Third Dynasty (1983), Nabil Swelim

attributed the Layer Pyramid to king Neferka, who had already 'completed'

the burial of his predecessor Nebkara at Zawiyet el Aryan North (Unfinished

Pyramid); (these two kings were placed by Dr. Swelim at the end of the

Third Dynasty, before Qa Hedjet- Huni). Swelim's view was focused on the

possibility that Z500 was a kind of northern-temple building for the unfinished

complex of Neferka, which was meant to imitate Netjerykhet's and Sekhemkhet's

complexes: the east-west orientation of this building seemed a tempting

motif to accept this view. He also advanced that some structures farther

to the east, stone ruins known as 'El Gamal el Barek', could have been

a proto valley temple; about this, Dodson writes that Perring describes

an "inclined approach from the plain beneath"; but the author

(op. cit., 87) leaves out such a possibility of an eastern causeway owing

to the too steep inclination of the surface east of the Layer pyramid.

No enclosure, which might have been in mudbrick, was ever noticed in the

ground and aerial surveys.

As seen, Z.500 is indeed a niched Mastaba with North-South orientation;

Nabil Swelim based this theory on the wrong assumption of a East-West

orientation of this building (as erroneously stated in Dows Dunham, 1978

p. 29); the Egyptian archaeologist later refined his view ('Rollsiegel,

Pierre de Taille and an Update on a King and Monument List of the Third

Dynasty' in 'Intellectual Heritage of Egypt - Studies Presented to Laszlo

Kakosy .... his 60th Birthday' Studia Aegyptiaca 14. 1992/ 541-554).

The opinion of Swelim about Horus Khaba (op.cit. p. 199 ff) is that this

king must be a close follower of Khasekhemwy, and surely to be placed

well before Sanakht and Sekhemkhet: this is shown by the earlier character

of the stone bowls of Khaba in comparison with those of Sanakht from Bet

Khallaf (Swelim used data provided by the important study on the Archaic

Egyptian Stone Vessels - from Predynastic to the Third Dynasty - published

by Ali el Khouli in 1978).

Finally the presence of bowls inscribed by Khaba around the pyramid could

be compared with similar practices later attested in Khaefra, Menkaura

and Sahura funerary temples, and previously witnessed in the enormous

amount of vessels preserved for Netjerykhet-Djoser: archaic kings' inscribed

stone vessels gathered for later sovereigns' funerary monuments.

The conclusions of Dr. Swelim (Some Problems,1983) for almost all of the

Third dynasty kings, including Khaba, do remain someway distant from the

mainstream of the currently accepted theories. Anyhow the field work and

the publications of this scholar bright among the most useful (and luckily

always more frequent) achievements of egyptology towards a more detailed

comprehension of the Early Dynastic period.

The site of Zawiyet el Aryan has been the object of two recent and important

studies: one by Mark Lehner and the other by Aidan Dodson (respectively

in P. Der Manuelian ed. 'Studies in honor of W.K. Simpson' 1996 and in

J.A.R.C.E. n.37, 2000).

The first study reveals that many photographs and sketches of the Boston

Museum of Fine Arts 1910-1911 expedition were still available, and publishes

a map of the Layer Pyramid based on a 1977 aerial photo. The orientation

of Z.500 is now definitively recognized as north-south, and not even in

axis with the middle N-S axis of the pyramid.

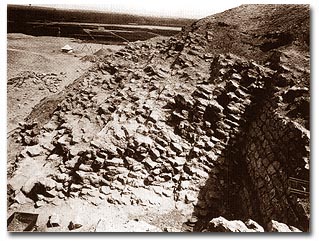

The tomb is a niched mastaba, as the photograph of page 521 shows; the

fact that it has no direct relation with the pyramid (which is more than

200 m from Z 500) doesn't affect the possibility of a link of the layer

pyramid with Horus Khaba.

In the most recent work concerned with the site in object, Dr. Aidan Dodson

re-examinates the problem from an archaeological and chronological point

of view. The second part of the study doesn't add much to the known situation:

the English scholar seems to be oriented in the traditional identification

of Khaba as one of the kings in the lacuna (hudjefa / sedjes)

of the Turin Canon and Abydos kings list respectively (but the table 2,

p.90 is fallacious because it places the lacuna between Nebkara and Huni,

while it is indeed between Djoserty and Nebkara).

Anyhow Dodson stresses the continuity between Sekhemkhet's and the Layer

Pyramid, showing how restricted is the slot into which the Layer pyramid

can fit.

The first part of the same study is very instructive for the knowledge

of the pyramid attributed to Khaba.

The author evidences once again, on the path already traced by Maragioglio

and Rinaldi's work, the discrepancies between the measurements of Barsanti

and those of Reisner as reflected also by their respective plans; he shows

that the former author is more reliable, possibly also because some parts

of the substructure were fulfilled again with sand in the 10 between the

two excavations.

Furthermore the main central gallery proceeds horizontally in its southernmost

course, after a part of it descends to the burial chamber, up to a point

directly above this chamber: this is shown in Barsanti's plan but not

in Reisner and Fisher's; nonetheless the American archaeologists must

have noted this feature because a photograph of theirs, which Dodson publishes

at page 84, has been taken just in front of the descending ramp with that

horizontal continuation of the main gallery (E1 in JARCE 37 p.82) in the

foreground.

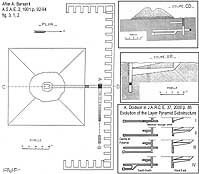

Dodson developes a possible evolution of the substructures of the

monument (see the 1st figure below, bottom right);

he also provides a logical explanation for the unusual eastern access

to the pyramid substructures, the only example of non- northern pyramid

entrance with the exception of Sesostri II's (and Snofru's at the Bent

Pyramid, where the main entrance is however the northern one, the western

gallery being a stand-alone additonal feature): the north-south main approach

ramp was substituted by one from the east not for topographical reasons

or, as Maragioglio and Rinaldi thought, to leave free space for building

the northern temple, but because the project of the pyramid of Sekhemkhet

had revealed the need for a fastidious expedient, a lateral narrow passageway,

to connect the main N-S corridor to the E-W storerooms.

(This solution is a further proof that the monument in object,although

constructionally simpler, is later than Sekhemkhet's one).

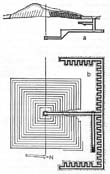

Plans and sections of the Layer Pyramid of Zawiyet el Aryan.

Compare the section of A. Barsanti with that of Reisner-Fisher :

There are many differences in galleries length and a whole gallery

(over the burial chamber) lacks in the Americans' map.

The empty burial chamber is m. 3,63 in length, 2,65 in breadth and 3,0 in height.

20 of these 'rooms' projects southwards from the east-west corridor and 6 on each one of the two north-south ending portions.

"La galerie inferiéure[?] était réservée à la reine,mais elle n'à pas été achevé non plus,et les galeries latérales n' ont pas recu les momies des princes ou des princesses à qui elles étaient destinées.Tant de travail a été en pure perte"(op.cit.,94).

Let's focus now on the following characters of this monument's project : the compact layers blocks in the core of the pyramid, perpendicular to the pyramid sloping side; the stores in comb shape; the funerary chamber and pyramid vertex perfectly aligned; these main features had been thought as an imitation of the Saqqara complex of Sekhemhet.